You Don't Need Aquarium Tests. Part 2

Detailed test review and conclusion

"Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results."

Albert Einstein

Read the beginning of the article

This article is a continuation of the first part with the same title "You Don't Need Aquarium Tests". If you arrived here without reading the first part, I strongly recommend following this link to familiarize yourself with it first.

Let's examine each test individually to better understand what we're talking about. I've arranged them in order from relatively useful to useless or even harmful.

TDS Meter

The more experienced an aquarist becomes, the more often they use a TDS meter (Total Dissolved Solids). This is a small electronic device that measures the overall conductivity of water.

TDS measurement itself gives practically nothing to a beginner. Conductivity means the sum of all ions contained in water: calcium and magnesium salts, fertilizers, fish waste products, and so on. What conclusions can you make if you see a value of 150 or 200 ppm on the device?

Many aquarists believe that a TDS meter is only needed to determine the condition of the osmotic membrane in a filtering system. Supposedly you control readings after the membrane, and when the TDS value increases — it's time to replace it. And it's useless for anything else.

But this isn't entirely true. Why do I refer to an experienced aquarist? Because only an experienced one can notice or suspect changes in the aquarium based on such a cumulative indicator. What's important is not the absolute value as such, but rather its change. An experienced aquarist knows well the water composition (or behavior) in their aquarium: what kind of water they have, how they prepare it, how many elements they add with fertilizers, how their hardscape react when CO₂ is supplied, and so on. When they immerse the device in water, they see a number already familiar to them.

But situations occur when readings suddenly differ greatly from usual. This is a good signal that some changes have occurred that could lead to problems. It's exactly the experienced aquarist, observing plant behavior and understanding well the general situation in the aquarium, who can conduct an investigation with good accuracy and identify the cause.

I'll emphasize again: the analyzing aquarist knows what they do day by day, week by week. By experience I mean specifically keeping a planted aquarium with additional CO₂ supply. If you had an aquarium with fish and plants without CO₂, that can be a good addition, but it's difficult to call it full-fledged experience for keeping an underwater garden. And here quality of experience is more important than number of years. Such an aquarist has no unpredictable processes, so they can immediately suspect from the general TDS indicator that something is going wrong.

Even just lowering a TDS meter into unfamiliar water, an experienced aquarist gets a starting point. As it was for me with tap water: I got a value of 32 ppm. Knowing approximately how much this or that hardness gives in ppm, I assumed that Kh would be 0-1, Gh 1-2. I refused drop tests, but subscribers of my YouTube channel asked me to take measurements, and I checked Kh and Gh. These were exactly the values in my source water.

Well, agreed, breaking down 32 ppm into components isn't such a difficult task. But if you have water with a value of 200 ppm, and you know that in your region there are aquarists with good planted tanks, then with high probability you can assume that the water will be ordinary and will have hardness within 3-4 KH and 7-8 GH. That is, we apply our knowledge to this measurement, gathered information, and make an approximate conclusion.

I'll give another example with my water. After rain I noticed that strong white deposits formed in the kettle. This prompted me to measure the water's TDS. And how surprised I was — the device showed more than 200 ppm! Now I collect water in advance when this indicator is around 30 ppm.

If we're talking about a tank on remineralized RO water, it's enough to lower the TDS meter after a water change, and you're already confident that you didn't make a mistake with the amount of remineralizer. This is what many famous aquarists with worldwide reputation do. Some don't even weigh Gh-booster, but simply add them to the aquarium until reaching a certain TDS value.

By the total TDS value we can judge the overall mineralization of the tank. As a rule, we more often see good tanks with TDS around 150 ppm or lower and less often — with TDS above 200 ppm.

Additional advantages of this device include that it's difficult for a beginner to harm the aquarium based on its readings. It's hard to start changing something if you poorly understand what exactly you're measuring. But it can still give reasons to worry unnecessarily — it's still a test. And if you're quite a suspicious person, this is a certain minus.

A TDS meter might give nothing immediately to a beginning aquarist, but you can start getting used to its use from the first steps. My recommendation is to have such a device. Only it's advisable to acquire a more or less quality model, not the cheapest one. And it would be good to check it on a solution with a known TDS value.

Kh and Gh - Tests for Carbonate and General Hardness

Water is hugely important in planted aquariums. This is often neglected or the importance of this factor is simply not realized. "Well water is water, poured from the tap and that's it" — no, this is absolutely not so. Water contains a very large number of elements that can be both beneficial and harmful to plants and livestock.

One of the primary indicators is water hardness: carbonate (temporary) and general (permanent). Permanent hardness (Gh — General hardness) is calcium and magnesium salts. Temporary (Kh — Carbonate hardness) is the amount of bicarbonates. Most aquarium plants prefer soft water in the range of 5-8 Gh.

In the case of tap water, you might not be able to do without Gh and Kh tests. With RO water (desalinated, with Kh and Gh equal to zero) everything is clear — we create water composition ourselves according to our desire, based on calculations and recommendations. The main thing is not to make mistakes with remineralization. But with tap water, if there are no acquainted aquarists, data from the water company, or simply no one to ask, you'll have to purchase Kh and Gh tests. But you'll need them only once, and their cost is relatively low.

Water hardness usually doesn't change much. Seasonal fluctuations are possible, but they're usually not very significant and shouldn't greatly harm plants. However, if water changes substantially in different seasons, then there can be no stability in the aquarium — here you can't do without a reverse osmosis system.

What possible harm can come from these two tests?

The main thing you shouldn't do, having hardness tests, is to rock the aquarium with constant changes in water composition. For example, if you dilute tap water with RO or use RO with remineralizer and regularly check hardness, you might encounter tests showing different values from week to week. In such a case, an inexperienced aquarist tries to "level" hardness, adding or reducing the amount of remineralizer, or changing the dilution proportion with RO if we're talking about tap water.

But the difference in readings might simply be measurement error, test mistake, or incorrect analysis. The test might turn out to be defective altogether. Thus, you create fluctuations in aquarium water parameters and thereby worsen conditions for plants and aquatic life.

In such a situation, it's better to make a small mistake with parameter selection (add slightly less or more remineralizer), but use the same amount from change to change. Let it be not 8 GH, but 9 or 7, but you'll maintain a stable value on a permanent basis.

I can't say that hardness fluctuations in a small range are a serious problem, but it's still better to avoid this.

Si - Silicon Test

The need for a silicon test is related only to several reasons: exceptionally poor water quality, unsuitable substrate, or problematic decorations in the aquarium. These are factors that need to be dealt with at aquarium startup — namely, study your water and don't add questionable materials to the aquarium.

The positive point is that cases of such poor water are quite rare. And you can control substrate and decorations yourself.

Diatom algae are a normal phenomenon for a new aquarium. Often they appear between the second and third week, and the aquarium will cope with them itself or with the help of snails and fish.

But if they appeared noticeably earlier — on the first week — and don't go away for more than a month, then you can take additional actions, up to restarting the aquarium and replacing substrate or changing water source. Making mistakes is normal. If you want to truly master this hobby, you'll have to start at least a dozen aquariums. I myself quite recently made a mistake with stones, and after two months had to restart the system. Removing problematic stones, I immediately solved the brown algae problem.

Therefore, if you purchase a test in such a situation, nothing terrible will happen. It won't force you to do something critically wrong. The main thing is that it shouldn't happen that brown algae are currently present naturally, but you, having bought a test, get inflated values due to its low quality or defect, and on this basis restart the aquarium unnecessarily.

pH - Water Acidity Test

The pH test is a practically useless test. Knowledge of this parameter gives you nothing. pH is water acidity. Plants like pH below 7 - slightly acidic water. Many measure the pH of tap water and say that the water has certain pH. They see high pH and on the advice of inexperienced people from the internet start adding various acids to lower pH. It gets especially funny sometimes with phosphoric acid. In attempts to reduce pH, the aquarist gradually increases phosphate in the aquarium to very high values, while pH in the aquarium will return to the initial value after a short time. And you'll have to get rid of phosphate for more than a month, since it's very strongly absorbed into the substrate.

Water doesn't have an independent pH indicator. As soon as you add a little carbon dioxide to water, pH already decreases. pH is a resultant value. Plants will grow not from low pH, but from the presence of CO2. And if there's gas, then pH will be low. Do you feel the logic? Where's the cause and where's the effect?

If Kh is adequate (from 0 to 6), then when supplying CO2, pH will be below 7 anyway. If you have high Kh and you supply CO2, then pH will also be high. If Kh is normal, then with proper CO2 supply, pH will be in the range from 5.5 to 7 anyway. What's the point of measuring it? There are no optimal values at which plants will grow better, or fertilizers that will be absorbed better at pH 6.5. Modern branded fertilizers withstand a large pH range thanks to strong chelators.

From my own experience, I haven't seen correlation between pH and plant growth. Here there's rather direct correlation between CO2 concentration and plant growth.

Some authors warn that when pH changes by more than 0.5 during the day, aquatic life might die. But actually here we need to look at the question more broadly.

Most fish that are commonly used in planted aquariums with CO2 tolerate pH changes over 2-3 hours (time from CO2 turn-on to maximum value establishment) by 1-1.5 units well. Such changes occur even in nature. Various tetras, for example neons or ember tetras, live well in acidic water. But mollies or guppies are better not kept in such aquariums. They prefer neutral or slightly alkaline water with medium hardness parameters. Therefore, when buying livestock, it's better to learn about keeping conditions for various species.

Since we're talking about livestock in planted aquariums, I'd like to give one piece of advice: don't get carried away buying expensive livestock in large quantities. You'll make mistakes due to inexperience, accept this as fact. Someday you'll overdose fertilizers, add excessive amounts peroxide, overheat the aquarium or give too much CO2, make very large and frequent water changes, very often replant plants, give very powerful light and thereby create excessive stress for aquatic life. They might even jump out of the aquarium. Part or all livestock might die. And worrying unnecessarily or changing aquarium conditions because of livestock can become a very unpleasant moment.

You'll already have a whole bunch of problems related to growing plants. Better to focus on this first. And when you get better at maintaining stable tank parameters and stressing livestock less, then you can buy more expensive and rare species. And for starters, free snails, cheap shrimps, or fish from local breeders will be quite sufficient to help clean the aquarium.

Denis Wong wrote very well about pH. The only benefit that can be extracted from a pH test is CO2 adjustment. But here you can manage without this, simply adjusting CO2 by aquatic life behavior, as recommended in their articles by ADA company.

What potential harm can come from a pH test? Let's say pH measurement showed an elevated level. You'll think that pH is too high for growing plants, and in such a case an inexperienced aquarist might follow advice to pour acid into the aquarium, add excessively large amounts of CO2, or take some other action destabilizing the aquarium.

Another example, but for increasing pH. There's an opinion that fertilizers (mainly this concerns micronutrients and iron) are absorbed better at pH around 6.7. And so you take a measurement, and the pH test showed a value of 6.3. What are your actions? The idea comes to mind to reduce CO2 amount and thereby raise pH. But in such a case, if at pH 6.3 livestock felt fine, and you reduce gas supply, then potentially in pursuit of fertilizer absorption you intentionally reduce CO2 concentration in water, which is element number one for plant growth. It turns out you're going in the opposite direction, when at the same time planted aquaristics strives for concentration to be as high as possible.

Well, you'll say: "Then we need to raise Kh! And thereby at the same CO2 supply and concentration in water, pH will rise" (we'll neglect bicarbonate equilibrium since it won't shift significantly in this pH range). Yes, that's right. But what if you have Kh equal to 0 for growing softwater plants, or you're growing Rotala Wallichii with maximum Kh 3 requirement? What to do in this case?

Or here's another task: what if you have soil substrate, and it acidifies water to pH 6.5 even without CO2? And when supplying gas, pH tends toward 6 and below altogether. What to do in such a case? At the same time, soil aquariums often look significantly better, and growing plants in them is easier.

The answer is simple: you don't need to level anything. Your fertilizers will withstand any reasonable pH range, and with such corrections you'll only make things worse. Ultimately, success will depend not on this, but on more important aquarium components.

It's quite possible that gas injection limitation will be more beneficial for your aquarium, and achieving maximum concentration isn't the best option. Such a situation is possible when water chemistry isn't very good, there's excessively much light, or for some reasons nutrition can't be absorbed to a greater degree than now. But it was exactly gas that didn't let plants grow faster, and nutrition was sufficient in such a situation. Giving more CO2, you weaken the limiting factor but don't eliminate the nutrition problem, and in such a situation plants might get worse. I observed this in my tanks due to poor substrate or fertilizer imbalance. This can be a good explanation for the reason plants worsen when CO2 increases, but also reason to think: is everything set up correctly in the aquarium?

Drop Checker

A drop checker is a small transparent drop-like reservoir with blue or green liquid. Less often with yellow. It's the closest relative of the pH test and is needed for determining CO2 concentration in water.

It's hard to imagine what harm it can cause. But there are nuances. Just as with the pH test, it can create wrong ideas about the amount of carbon dioxide in water.

From manufacturer to manufacturer, the reagent and shape of the device itself differ greatly. And CO2 level indication can vary substantially.

Readings strongly depend on drop checker placement in the aquarium. And with good gas dispersion, such an optimal place might not exist at all. Fine CO2 bubbles get into the drop checker and makes it more yellow, consequently you'll reduce gas amount and move the aquarium away from optimal condition.

The reagent needs to be changed regularly. A beginning aquarist might not even know about this.

The drop checker is very inert. It will show equilibrium gas concentration values only after 3-4 hours after CO2 is already at peak. And the peak, as we remember, comes 2-3 hours after gas supply starts. This can create false impression that gas accumulates during the day and by evening will be at critical point, due to which aquatic life might die. No, this isn't so. If you set good gas supply and created strong surface agitation, then even round-the-clock CO2 supply won't harm livestock (in my 35-liter aquarium, my solenoid didn't turn off gas for the night several times, and at 2 bubbles per second no one in the tank died). This happens because plants don't consume even one percent of the total gas amount. Almost all CO2 simply runs out of the surface. Thus, gas concentration with and without light won't differ by practically anything.

Another misconception is that the drop checker will protect your livestock from excessive CO2. But actually, by the time it reacts to gas increase, all aquatic life will already have gone to Neptune. I encountered this myself. When I noticed all livestock on the water surface, the drop checker was still green.

Even ADA's recommendation for gas supply is that you need to start with 1 bubble per second for a 60-liter tank and observe plant growth, not ask the drop checker hanging in the aquarium corner. With any gas manipulations, you need to be near the aquarium and have the ability to fix the situation. Unfortunately, it happens that gas increases uncontrollably due to equipment malfunction, and usually you won't be nearby at that moment.

NH3 and NO2 - Ammonia and Nitrite Tests

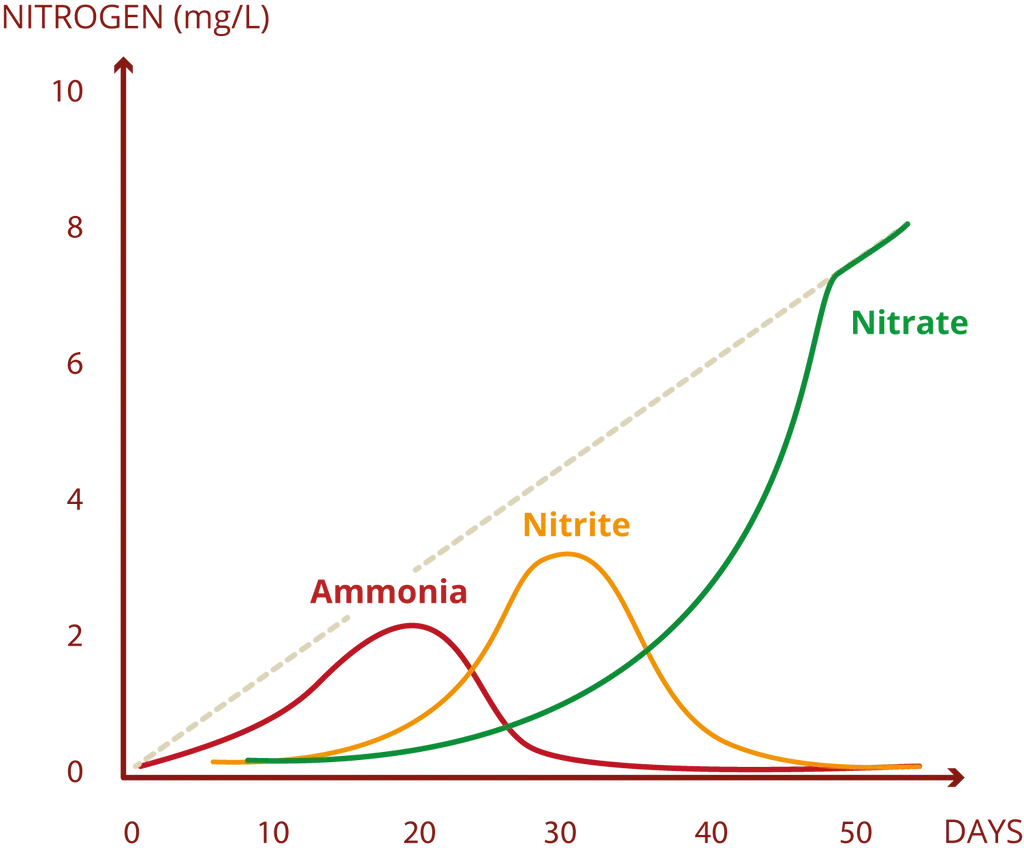

Everything is very simple here — pay attention to establishing the nitrogen cycle. These elements will be present at startup anyway. And only time is needed for all toxins to be processed into relatively safe nitrate. No water changes can help you at this moment. Water changes reduce toxin levels but don't eliminate them completely.

Image taken from Denis Wong's article.

When the aquarium has established the nitrogen cycle and you don't make very gross mistakes such as sudden relocation of large numbers of fish, overfeeding, or poor filtration, then ammonia and nitrite indicators will always be at level 0.

Cu, Cl - Copper and Chlorine Tests

Be reasonable in your expenses. The main thing is don't use poor quality materials for decorations in the aquarium or try to save money using very cheap substrate in the aquarium.

Fe - Iron Test

I'll classify this test as useless or potentially harmful. Its harmfulness lies, like with any tests, in creating false impression of control, unnecessary fuss, and erroneous conclusions.

The idea of measuring iron and thus tracking micronutrient absorption dynamics seems good, since they're usually dosed by iron. But iron is an extremely unstable element in water. Its stability is increased by chelators. But setting up iron measurement with a test depending on the type of chelator used is a very complex and unnecessary task.

On the other hand, if you decide to dose micronutrients based on iron test readings and conclude that micronutrients are already consumed and need to add more, this road will lead you to micronutrient overdose if you deviate significantly from manufacturer recommendations. And this is most dangerous for plants — poisoning them with heavy metals.

K - Potassium Test

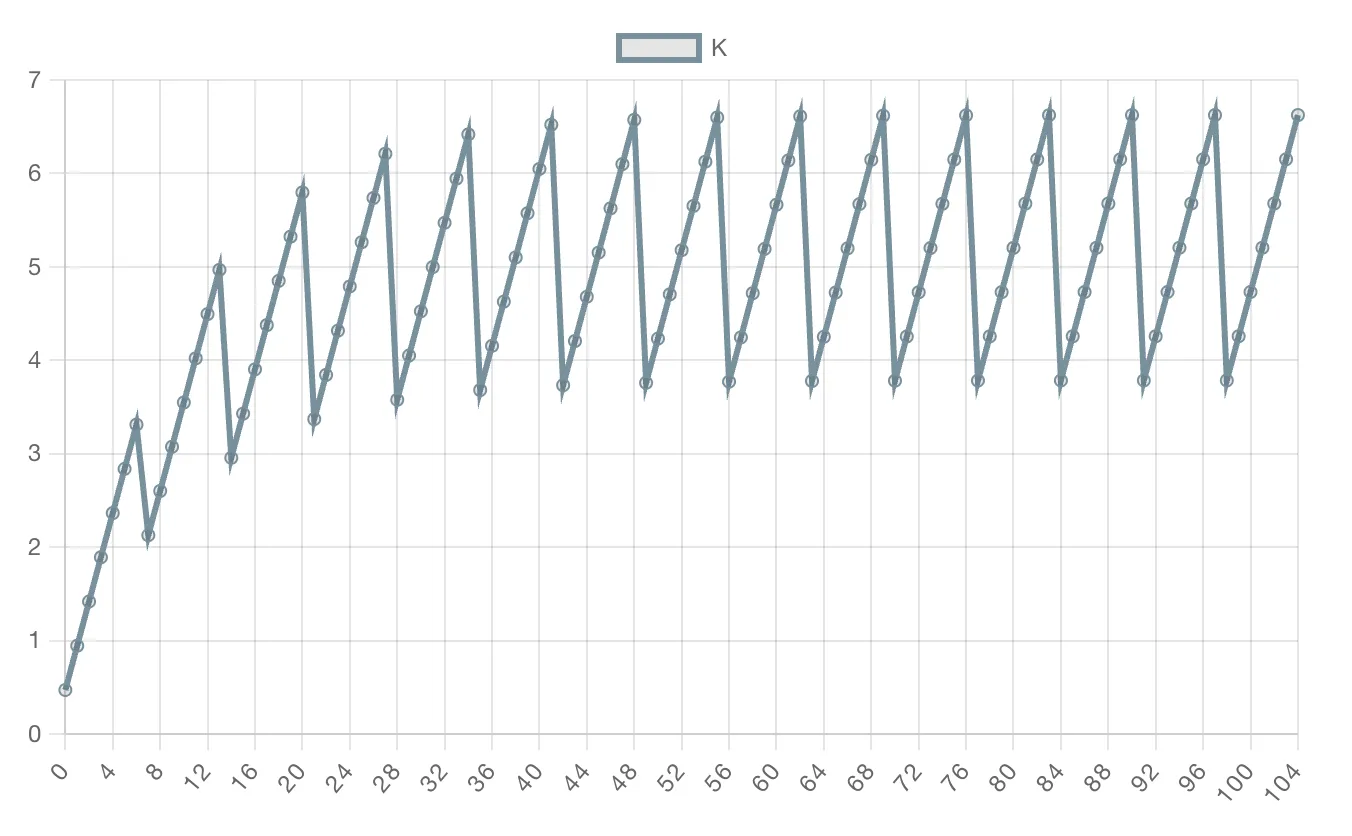

I'll save you a lot of money and time. I wrote about potassium in detail in another article. In short, on neutral substrate it's enough to use the formula:

This will give you equilibrium concentration, the one that will establish after a month or two if you maintain the same water change and dosing regime.

You can also view the potassium change dynamics on the dosing page in the «Tank Parameters» popup window to get a more detailed understanding of how the concentration changes.

On soil substrate, you can additionally divide this value by 1.5-2, since soil often absorbs potassium.

You'll ask: "But how can this be? Plants consume potassium. Concentration will decrease." No. They don't consume — at least in amounts that a test can measure, we can consider they don't consume. Good potassium tests have very rough measurement scales. And no matter how much I measured, the test doesn't show any potassium changes during the week on neutral substrate. And even if plants do consume potassium, we're more afraid of overdose than deficiency. And it's better to underdose potassium than overdose. I wrote more about potassium deficiency and dosing strategy in this article.

How do I know you can simply calculate with a formula or graph? I did tests myself and compared with the graph. And not only me. And not only with store tests, but also laboratory ones.

NO3 and PO4 - Nitrate and Phosphate Tests

And here we've reached the root of evil 🙂

I'll consider both elements since they most often come in pairs in fertilizers, discussions, etc.

What dangerous thing can there be in such simple elements? Actually nothing super terrible, but in aquarist conclusions regarding test measurements — there is.

I'll describe how tests are most often used. Most often aquarists consider it necessary to first understand how much nitrate and phosphate is consumed daily in their planted tank. And so the aquarist takes a nitrate test, takes a measurement in the morning and takes a measurement in the evening, then trying to calculate daily consumption. This action has several potential problems.

First, test accuracy. No one nitrate test in wide consumption will accurately measure the difference for you. Test error is at best 2-3 mg/L, or even 5. On some scales, marks are at values 0, 10, 25. How do you like such accuracy?

Second, test error isn't the worst thing. The worst thing is that tests often simply lie or don't work at all.

Third, aquarium consumption can change and will change. There's dependence on many aquarium settings or simply trimming. You'll have to recalculate consumption even if you already found it and managed to do this quite accurately.

And imagine you measured 10 nitrate in the morning, and in the evening you have 5 on the scale. How much nitrate will you add the next day? You'll probably try to add 5 nitrate. You add fertilizer to 10, measure in the evening. And nitrate is already not 5 as expected, but 10. "Well then I won't add since the aquarium didn't consume anything," — you think. And you either add fertilizers or don't. But the aquarium needs stability, any experienced aquarist will confirm this.

My friend's test showed nitrate in tap water more than 20. It's not hard to guess what conclusion he made — no need to add nitrate. And he added only phosphate. Only algae grew, not plants. But for some reason when he started adding nitrate, plants came alive. Interesting thing, isn't it?

Moreover, tests might not work at all! And due to your inexperience, you'll believe the reading. Because you can't even think at this stage that tests made by smart people might not work. How many aquarists, hoping to see the coveted 1 phosphate unit, saw transparent liquid instead of blue and started pouring phosphate like crazy, blaming the fertilizer manufacturer for poor quality or thinking that the aquarium consumes so much fertilizer!

Recognize yourself? You think: "Need to add fertilizer!" You add. Again 0. "Need more!" You add even more! And so until algae appear. I fell for this myself, with a very good German test. What can be said about cheap ones!

You're unlikely to poison livestock with nitrate, but this won't make them more healthy. And the opposite happens. There's no nitrate, but the test shows 10-15 mg/L. "Well then no need to add." Meanwhile plants will start starving and algae come again.

The nitrate test is capable of much. You can check it on a reference solution. And the next measurement in a couple days will already be wrong because it simply spoiled. Or it can easily show 10 nitrate in fresh RO and 0 in the same RO that has sat. Miracles.

And it gets more interesting when the aquarist has two different bottles with nitrate and phosphate, and does tests for nitrate and phosphate in the aquarium. Oh, here it begins! One test showed one thing, another showed another. We start regulating the ratio. And tomorrow measurements became very different due to the above, and again we add one, don't add the other.

We try to level something in the aquarium. Meanwhile plants stop growing or deteriorate, and that's it.

But if we pose the question from another side:

Why did we at some point decide that we need to test nitrate and phosphate? You don't test micronutrients. And the answer is simple: yes, simply because such tests are available in the store.

But then how to add fertilizers if I don't know how much of what is there and overdose might occur? It won't occur. If you give the recommended dosage and do water changes. Believe me, this is more reliable than coming in with your "knowledge" from the internet and leveling. You can take recommendations from different manufacturers, and most often you'll encounter nitrate dosage around 6-7 ppm, less often closer to 10 ppm per week.

Yes, dosages aren't ideal, but better than tests in that you can control them. You create consistency in the tank, and plants will get used to it anyway. Yes, some won't grow very well. But it's better to simply get rid of such species. And you even need to get rid of them! This is normal. You can't make everyone happy. And you have a very reliable remedy against excess fertilizers — water changes.

"But I was told I need to have Redfield ratio in water!" You don't need to. Everything is already accounted for in fertilizers, and how balance will establish in the aquarium, trust nature itself. Don't think you're smarter than the manufacturer of good and proven fertilizers.

If you think your plants are starving and need to be fed, here's my aquarium with only 6 ppm nitrate per week:

Conclusion

I agree that the problem is exacerbated by the fact that wherever you come with your problem, the first thing you'll be asked is: "What do the tests show?" Everything pushes you toward this. This is why I'm writing this article, not to push you onto this path, but to show an alternative way of keeping an aquarium.

Without tests you focus on other things and worry less. Pay attention primarily to setting up the whotel tank, not tests and fertilizers. Make sure that:

- light power is correct

- CO₂ is sufficient

- water is good

- there are no harmful materials in the aquarium

- sufficient plants are planted

And only after this, take fertilizers and add strictly according to manufacturer recommendations.

Control what you can control. Don't dig too deep. Usually the problem lies somewhere on the surface. It's like getting under the car hood and trying to fix it before you learned how to drive. I suggest finding the steering wheel and pedals in the aquarium and learning to drive, and trusting repair to professionals.

The problem with the measurement-related approach is that you'll achieve success only when you study all aspects. And this is definitely not given to everyone, and not everyone will want to do this. Are you ready to read scientific books on botany, chemistry, plant physiology, etc.? But observing plant behavior is something available to everyone from the first days of aquarium existence. And your intuition can give results much faster.

Someone might call such an approach unscientific. But I would call it purely practical. You saw yourself the tanks above. How did people manage to achieve such beauty? In aquaristics you can say thousands of words, but your interlocutor's aquarium will speak for itself better.

Think for yourself how much can be changed in an aquarium: light, water, CO₂, plants, livestock, substrate, filter, decorations, fertilizers — and here we also add tests, which are a very unreliable link between you and plants. Just decide for yourself, do you even need such aquaristics? What do you want: to admire the aquarium more or run around it with test tubes?

I'll honestly tell you that the path of observing plants is long and sometimes painful, but with tests you'll simply walk the same circles year after year and never get anywhere.

Here are examples of my aquariums that I kept without tests. You can see their complete history on my YouTube channel.

If you have at least 2 aquariums and use tests, then simply try not using tests in one of them. Although, it might be very difficult to stop yourself from grabbing tests in moments when problems start in the aquarium, if tests are lying on your shelf.

Want to discuss the article? Go to our Telegram channel.